Invisible Poison in the Air: How Gold Mining Is Contaminating African Food Crops

A new study has revealed something both surprising and alarming: the food people grow near small gold mining sites in Africa is being contaminated — not through the soil as scientists long believed, but directly from the air.

This discovery, published in the journal Biogeosciences by the European Geosciences Union (EGU), shows that mercury — a toxic metal used in small-scale gold mining — can travel through the air and get absorbed by plants.

The gold rush and its hidden cost

Across many parts of Africa, Asia, and South America, thousands of people depend on artisanal and small-scale gold mining (ASGM) to earn a living. These miners often use mercury to separate gold from rock. The process is cheap and easy — but extremely dangerous.

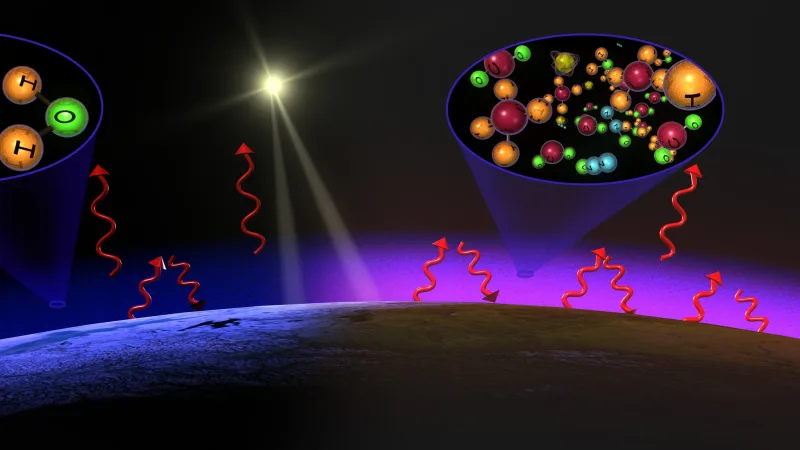

When mercury is heated or spilled, it evaporates into the air as an invisible gas. Once in the atmosphere, it can travel long distances before settling on land, water, and crops.

Over the past 25 years, the price of gold has increased more than tenfold. This has triggered a mining boom in many poor regions — and with it, a rise in mercury pollution.

Breathing in mercury: what the study found

The research team, led by Excellent O. Eboigbe and David McLagan from Queen’s University in Canada, and Abiodun Odukoya Mary from the University of Lagos, studied farms near a gold mining area in Nigeria.

They compared two sites:

- One just 500 meters from a mining area

- Another 8 kilometers away

The difference was startling. Crops grown near the mining site had 10 to 50 times more mercury than those farther away.

But what surprised the scientists most was how the mercury got into the plants.

For decades, experts assumed mercury pollution entered crops mainly through their roots — when it seeped into the soil or water. However, this new study found that most of the mercury was entering through the leaves, as the plants absorbed air during photosynthesis (the process plants use to take in carbon dioxide and release oxygen).

In other words, plants are “breathing in” mercury from the air.

Why this matters

Mercury is a powerful neurotoxin — it attacks the brain and nervous system. Even small amounts can harm unborn babies and young children, affecting learning, memory, and movement. It can also cause long-term damage to the heart and reproductive system.

While the study found that mercury levels in the crops were still below international safety limits, it warned that people who live near mining areas and rely on local food might still face health risks over time.

Leafy vegetables (like spinach and cassava leaves) were found to hold the most mercury. Even root crops like cassava and maize, which had lower levels, still showed contamination.

A bigger problem than we thought

According to the UN Environment Programme, small-scale gold mining is now the largest source of mercury emissions in the world.

Yet most governments and international organizations only test mercury levels in fish, water, or sediment — not in crops. That’s a serious gap, says the research team.

Dr. McLagan explains:

“Plants that remove mercury from the air are performing an important service for the planet. But when those plants are food crops, that same service becomes a threat to human health.”

What can be done

One of the authors, Dr. Odukoya, emphasized that miners won’t stop using mercury until they have an affordable and easy alternative for gold extraction. That’s why governments and global organizations need to step in — not just to ban mercury, but to support miners with safer technology and better education.

The study also calls for new monitoring policies under the Minamata Convention on Mercury, an international treaty aimed at reducing mercury pollution. Policymakers, the researchers argue, must now include agricultural crops as part of their mercury monitoring systems.

A silent crisis in the making

Millions of people across Africa and other developing regions depend on local agriculture for survival. This study shows that even when the soil looks clean and the air seems fresh, toxic metals may be silently entering our food.

It’s a reminder that the costs of the gold rush go far beyond the mines — reaching into kitchens, dinner tables, and human bodies.

You can find the original study here.

About the author: Mohsin Rasheed is the Co-Founder and Chief Editor of Everyman Science, dedicated to making complex scientific ideas simple and accessible for everyone. You can reach him at [email protected]

Photo: Gold mining in Nigeria. Photo by Dame Yinka. Source: Wikimedia Commons